12 Aug Two Women and a Sporting Book Collection

Two Women and a Sporting Book Collection

by Ann Havemeyer

Most people have heard of Orvis, the fly-fishing and wingshooting international retailer headquartered in southwestern Vermont. But are you familiar with Mary Orvis Marbury, author of the 1892 fly-fishing book Favorite Flies and Their Histories? Or Paulina Brandreth, who wrote Trails of Enchantment (1930) under the pseudonym Paul Brandreth? Both books are housed in our Rare Book Room as part of the Frederick Sprague Barbour Collection of hunting and fishing books.

The Barbour Collection was developed by Frederick K. Barbour (1894-1971), an avid sportsman. Barbour and his wife Helen Carrère Barbour were summer residents of Norfolk, having been first invited here by Helen’s cousins, Reginald and Beatrice Carrère Rowland. Like many of the early summer residents, Reg Rowland and Fred Barbour were attracted to Norfolk for its excellent hunting and fishing opportunities. In addition to upland birds and deer, the many streams and lakes were filled with trout, perch, pickerel, and bass.

The Barbours’ son Frederick Sprague Barbour (1927-1952) was a second lieutenant in the Field Artillery at West Point during the Korean War, when he died of bulbar polio in 1952. His interest in hunting inspired the bequest of the Barbour Collection in his memory. Among the many first editions in the collection, those by Mary Orvis Marbury and Paulina Brandreth stand out. Both Marbury and Brandreth were influential women in their respective sports of fly fishing and deer hunting, and their landmark books are still in print today.

Mary Ellen Orvis Marbury (1856 -1914) was born in Manchester, Vermont, the oldest child and only daughter of Charles F. Orvis. In 1856, the year of her birth, her father founded the C. F. Orvis Company, now known as the Orvis Company, and established a shop selling fly-fishing rods and flies made by the company.

Marbury graduated from the local high school in 1872. Shortly thereafter she expressed an interest in fly tying, so Orvis brought New York City flytier John Hailey to Vermont to give tying instruction. As a student Marbury did well, and in 1876 she became the manager of the company’s fly-tying operations. That same year she won first prize for an exhibit of flies at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

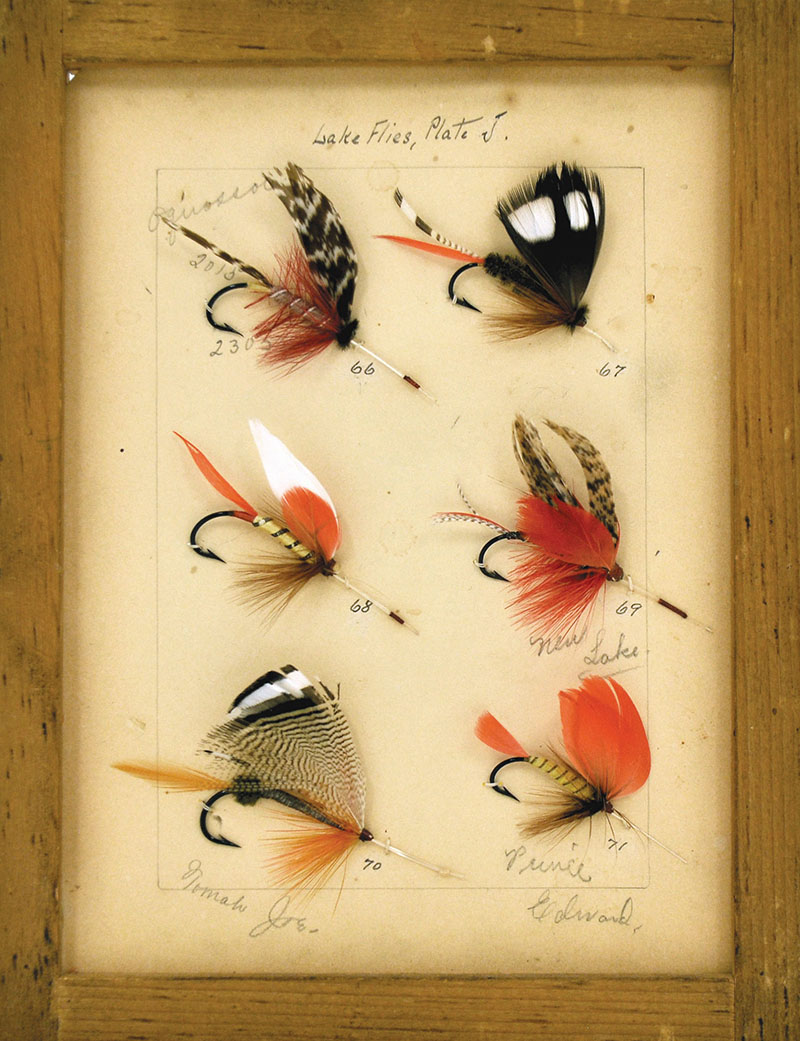

A trout fly plate that served as a model for the chromolithograph in Marbury’s book (Collection of the American Museum of Fly Fishing)

The women of Orvis’s fly-tying shop in the 1890s (courtesy of the Orvis Company)

Marbury hired local women and trained them using patterns that were based on British styles, slightly changed to suit angling in this country. By 1890, the company was tying and selling more than 400 different fly patterns. In order to create a fly-pattern standard for fishing in North America, Marbury compiled a list of patterns used in different regions of the country and created a book that would set the standard for name and pattern according to location. The landmark Favorite Flies and Their Histories was published in 1892. By 1896, there had been nine printings.

The full title of the book is descriptive: Favorite Flies and Their Histories. With many replies from practical anglers to inquiries concerning how, when and where to use them. Illustrated by Thirty-two colored plates of flies, six engravings of natural insects and eight reproductions of photographs. 291 patterns from Canada, thirty-six states, and two territories (Arizona and Utah) are included. To complement the book and to represent the C. F. Orvis Company at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Marbury assembled hinged fly panels for public viewing. These panels would one day become the inspiration for the founding of the American Museum of Fly Fishing in Manchester, Vermont. For her work on Favorite Flies and Their Histories, Marbury is lauded as one of the most influential women in the sport of fly fishing.

Equally notable was Paulina Brandreth (1885-1946), an accomplished photographer, hunter, naturalist, and writer. Brandreth hunted and photographed deer on her family’s 24,000-acre property in the Adirondack Mountains of New York. She often went afield with other well-known hunters of the day, including Roy Chapman Andrews, General “Black Jack” Pershing, and Reuben Cary. Andrews was an explorer and naturalist, who led a series of expeditions to the Gobi Desert and Mongolia in the 1920s. He would later serve as Director of the American Museum of Natural History, before retiring in 1942 to his home in Colebrook, where he wrote most of his popular autobiographical books. Two of his titles are in the Norfolk Library collection.

Brandreth began writing for the sportsmen’s journal Forest and Stream in 1894 at the age of nine. Her material was credited to “Camp Good Enough, Brandreth Lake,” which was a deer camp on land purchased by her grandfather for hunting and fishing. As an adult, Brandreth continued to write, using the pseudonym Paul Brandreth. A woman hunter of her era was a rarity; even more so was a woman writing about hunting. In a 2003 foreword to Trails of Enchantment, Robert Wegner writes, “Of the more than 2,000 books written on the subject of deer and deer hunting…, only five are written by women.” By writing with a pseudonym, Brandreth was able to publish books on hunting, fishing, conservation, and camping in the wild, as well as 31 articles in Field and Stream and Forest and Stream magazines.

Trails of Enchantment was published in 1930 by G. H. Watt, a New York-based publisher. A review in Gray’s Sporting Journal noted the many “gems” in the book, especially the concluding chapter “The Spirit of the Primitive,” described as “one of the finest essays on the wilderness ethos and should appear with Aldo Leopold.”

Considered by many to be the father of wildlife ecology, Aldo Leopold was an ecologist, forester, and environmentalist, who wrote A Sand County Almanac in 1949. His Land Ethic essay was published as the finale to the book. It is a call for moral responsibility to the natural world. As described by the Aldo Leopold Foundation, a land ethic expands the definition of “community” to include not only humans, but all of the other parts of the Earth as well: soils, waters, plants, and animals. In this community, people care about people, about land, and about strengthening the relationships between them. In Trails of Enchantment, Brandreth wrote about the experience of communing with nature. The book is still considered one of the best ever written about whitetail deer.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.