12 Aug Norfolk: Town with a Strange Personality

Norfolk: Town with a Strange Personality

by Ann Havemeyer

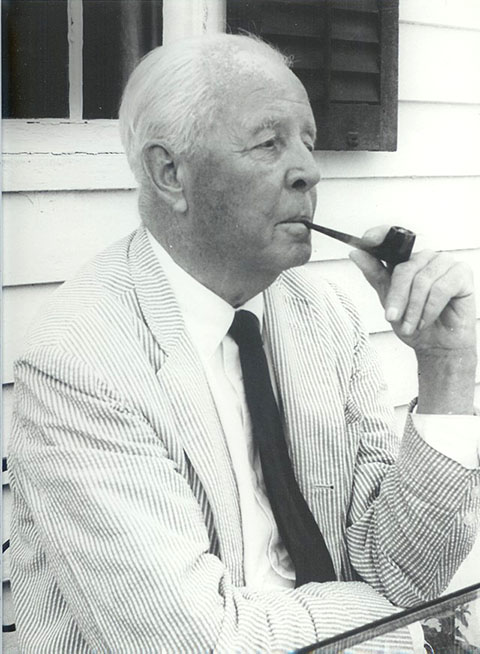

Philip Curtiss (1885-1964)

A century ago, Norfolk was emerging from the heyday of its summer resort years. Many of the hotels would soon close their doors. The internationally-recognized Norfolk Festival concerts would end in 1925, and in 1927 the Central New England Railroad would stop all passenger service to Norfolk. It was now time to take stock of the town’s identity, as was done in the late 19th century when Norfolk was faced with the decline of industry and had to reinvent itself as a summer resort to remain vital.

The writer Philip Curtiss (1885-1964) did just that. His family had lived in Norfolk for six generations. Born and raised in Hartford, he began work as a reporter for the Hartford Courant before returning to Norfolk in 1917 to live full-time in the old family homestead on the Curtiss farm at the corner of Mountain Road and Golf Drive. There Curtiss wrote articles for Harper’s Monthly Magazine, Scribner’s Magazine, and Ladies Home Journal along with novels and plays. He was described in Who’s Who Among North American Authors as an author of “general character writing, novels of village life, and light comedies or burlesques in mystery style.” (vol. IV, 1929-1930, 257).

Curtiss’s move to Norfolk was part of a statewide trend of decamping to the country, made possible by improved transportation, decentralization of employment opportunities, and advances in technology. Sound familiar? The rural population of Connecticut doubled between 1900 and 1950. The United States Census recorded a seventy-five percent increase in the population of Norfolk between 1920 and 1980.

In a June 1935 article for Harper’s Monthly Magazine entitled “They are moving to the Country,” Curtiss addressed the migration of city people to this “mountain village.” He defined these “back-to-landers” as residents who did not maintain a home elsewhere, and counted them to make up nearly ten percent of the families in Norfolk at the time. Ostensibly perplexed by the question of why city residents would choose Norfolk as their primary home, Curtiss humorously tapped into the legend of the town’s isolation and forbidding natural environment, and began to develop a revised identity for the town:

“To realize the full significance of the new state of affairs it must be noted that our particular town is somewhat isolated and quite severe in its climate. The nearest large city is New York, which can be reached only by a drive of nine miles, followed by a journey of three and a half hours on the train, or by a drive of twenty miles and a train journey of two and a half hours. A temperature of thirty degrees below zero is not unusual and for weeks at a time the thermometer will hover between ten below and ten above.”

Yet it was not only the town’s isolation and natural environment that played into its identity, it was something more, something Curtiss found hard to put into words. In an article for a local magazine The Lure of the Litchfield Hills, Curtiss described Norfolk as a town with a strange, distinct personality:

“The real truth is that from the earliest times the town of Norfolk seems to have had a strange, distinct personality of its own, a thing quite impossible to explain. Whether it lies in the thin, clear quality of its mountain air (which is physically noticeable as you drive up to Norfolk from any direction), whether it lies in the rugged beauty of its tumbled, wooded hills, or whether it is some local spirit which it is impossible to analyze, one cannot say, but it is distinctly there.”

Curtiss painted a picture of the town, aligning it with his romantic image of colonial days when those who sought richer farm lands left town, and those who remained chose the “dignified, quiet” social life:

“There have never been, for any long period, any of those vivid, blatant sources of gayety which make and unmake the reputations of more gaudy resorts. There has been no beach—for obvious reasons; no large hotels, no sporty or smart set, no race track, no airplanes, no motorboats, and a dance in Norfolk is usually about as exciting as a strawberry festival. The result has been in modern days what it was in Colonial—that those who demand gayety in visible forms or those who expect a definite result for every effort have speedily left town. Those who have remained are those who, precisely, have found some heart-tug in the region itself—who have loved its hills, its woods, its dignified, quiet social life, or who, without asking a reason, have been caught by that indefinable thing that is known as “Norfolk.”

Curtiss’s article appeared in 1930, the year that his friend and fellow writer Sinclair Lewis won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Lewis’s most famous book Main Street had been published in 1920 to great acclaim and was juried for the Pulitzer Prize, although it lost to Edith Wharton’s Age of Innocence. Main Street satirized small-town life in Gopher Prairie, Minnesota, a fictionalized version of Sauk Centre, the author’s hometown, and it was an enormous commercial success.

A year after its publication, Lewis visited Curtiss in Norfolk. The two writers were the same age and had begun their careers working for newspapers. One can only imagine the conversation that must have ensued between them as they sat in the parlor of the Curtiss home in the small town of Norfolk. Lewis did sign his name on the ceiling of the parlor, as had other writers, but he did not record his impressions of Norfolk small-town life. He did, however, give inscribed copies of his book to several town residents, including Augustus P. Curtiss, who operated a local livery service and picked up Lewis at the train station. He wrote:

“To. Mr. A.P. Curtiss with the wish that I could practice my art as well and as generously as he does his! Sinclair Lewis. August 3, 1922.”

The Library has six novels by Philip Curtiss, published between 1915 and 1929.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.