23 Jul The Summer Colony

Built in 1892, the Eldridge Gymnasium had two grass tennis courts, where tennis tournaments were held, including the Connecticut State Tennis Championships in 1915.

The Summer Colony

by Ann Havemeyer

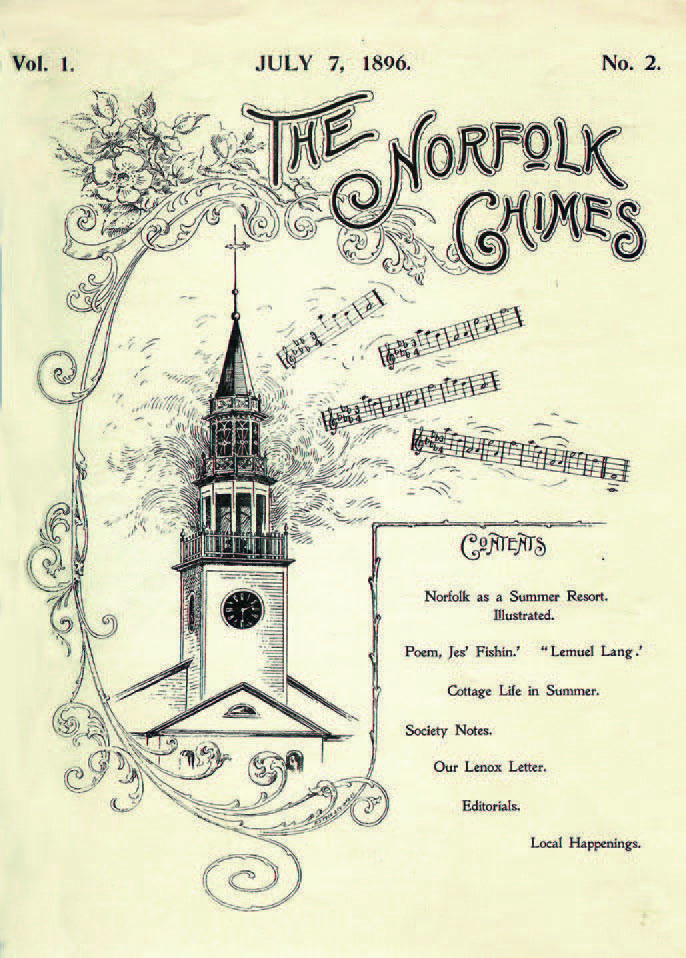

Among the Norfolk Library’s collection of rare books and historic artifacts is a complete set of The Norfolk Chimes, a glossy magazine published weekly from the end of June to Labor Day during the summer seasons of 1896 to 1900. Despite the magazine’s short run, it presents a fascinating glimpse into the life of Norfolk’s summer colony at that time. A burgeoning resort, Norfolk attracted many visitors, and each issue of the Chimes included a list of the new arrivals.

Among the Norfolk Library’s collection of rare books and historic artifacts is a complete set of The Norfolk Chimes, a glossy magazine published weekly from the end of June to Labor Day during the summer seasons of 1896 to 1900. Despite the magazine’s short run, it presents a fascinating glimpse into the life of Norfolk’s summer colony at that time. A burgeoning resort, Norfolk attracted many visitors, and each issue of the Chimes included a list of the new arrivals.

Norfolk’s identity as an attractive resort was carefully marketed in the Chimes. The editors observed that it was a certain “class of citizens” that was responsible for Norfolk’s genteel character as a resort: “They are people of education and refinement, professional and literary men, who give a distinct and high character to the town, and will continue to do so unless by some unhappy chance Norfolk should lose this valuable class of citizens, and throw itself into the arms of the Philistines, whose ambition is to make it a ‘picnic resort’ and a ‘city of hotels,’ to change the good old Anglo-Saxon word ‘road’ into ‘boulevard,’ and commit all the atrocities which would turn our fair village into an inland Atlantic City.”

Author William Dean Howells described the social stratification among resort towns on the southern coast of Maine with light-hearted humor: “Beyond our colony which calls itself the Port, there is a far more populous watering-place, east of the Port, known as the Beach, which is the resort of people several grades of gentility lower than ours: so many, in fact, that we can never speak of the Beach without averting our faces, or, at best, with a tolerant smile.”

With vacation communities divided by distinctions of class, religion, and ethnicity, where would Norfolk fall in the spectrum of resorts? Just as Norfolk abhorred the idea of becoming another Atlantic City, so was it careful to distinguish itself from nearby Lenox and the wealthy cottagers who summered in the Berkshires. “Although there is wealth and beauty in Norfolk,” the Chimes editors wrote, “and plenty of gaiety, the town is noticeably free from that social stiffness which pervades the atmosphere of the popular resort of so many from New York’s ‘Four Hundred.’”

Visitors to Norfolk had their choice of accommodation. They could spend a week or more in one of the town’s popular hotels, such as the Hillhurst on Laurel Way or Crissey Place on the Village Green. Townsfolk often opened rooms in their homes to capitalize on the possibility of extra income. These were the Airbnb’s of the late 19th and early 20th century. Farmers in the south Norfolk neighborhood of Grantville advertised the rural experience to attract weekly guests.

On Grant Street, photographer Marie Kendall offered rooms in her house, which she named Edgewood Lodge. In 1906, she placed an advertisement in The Connecticut Magazine designed to attract attention. In bold lettering, Norfolk is described as the Switzerland of Connecticut: “Distinguished globetrotters say that in the Hills of Norfolk, Connecticut, Nature’s Art has an individuality of its own. Well-known Americans come hundreds of miles to sojourn in this hill-top Garden-land and breathe its pure invigorating air.” Kendall was careful to insist that only “cultured people” were guests at Edgewood Lodge. She described her house as “a modern, private, hospitable home; sanitary, home-like, heated by hot water; located within a two-minute walk of a thoroughly equipped library and less than a five-minute walk to the post-office, church, gymnasium, and railroad station.”

The proximity of Edgewood Lodge to the center of town was indeed an attraction, with tennis, bowling, and evening concerts at the nearby Eldridge Gymnasium (now Town Hall). Lodging on Maple Avenue was even more desirable. Some residents temporarily relocated to make their Maple Avenue “cottages” available for rent to summer cottagers.

Many of the cottagers would go on to purchase property and build their own houses, becoming fulltime summer residents. They are listed in a small booklet published by the Village Improvement Association between 1900 and 1905 entitled

“What’s in a Name?” For a small contribution, summer residents were listed along with the names of their houses, for every house had to have a name.

The Alders, now known as Manor House, was the home of Charles Spofford. Spofford designed the Underground Transit system in London and was the son of Ainsworth Spofford, the first Librarian of Congress. On Laurel Way, Laurelese was the residence of James Mabon, president of the New York Stock Exchange. Next door, the Breezes was built by Abel I. Smith. His son would later fund the construction of the Smith Children’s Room at the Library.

Abel I. Smith’s father was one of the earliest summer visitors to Norfolk. An attorney and district court judge from Hoboken, NJ, he was invited to “this charming mountain village” by Alfred Dennis in 1870. To get here at that time, he had to travel by steamboat from New York to Bridgeport, take the Naugatuck Railroad to Winsted, and then drive to Norfolk.

Alfred Dennis lived in a house overlooking the Village Green. His son, Dr. Frederic Shepard Dennis, wrote a book about the Village Green in 1917 (available at the Library). He dedicated it to his mother, Eliza Shepard Dennis, “who was born in a house near the Green, who played in her childhood upon the Green, who was married in meeting house facing the Green.” Dr. Dennis was a professor at Columbia University, and his estate is now Dennis Hill State Park. He was one of several Columbia professors who summered in Norfolk.

Other Columbia professors included Michael Pupin, Professor of Electro-mechanics, who built Hemlock Farm on Westside Road (now the home of the CT-Asia Cultural Center); and Henry Todd, Professor of Romance Languages, who engaged architect Alfredo Taylor to design his house Brocklebank on Litchfield Road. Across the road from Brocklebank stood Elmslea, the summer home of Professor Gustave Stoeckel of Yale University. In the Chimes, the Reverend John Calvin Goddard described those who gave “a distinct and high character” to the town: “You could stock a university faculty or man a metropolitan pulpit any day in August without going off the veranda of the Hillhurst hotel.”

Yet all were not upstanding citizens. Mrs. Margaret Mulhall built a summer residence on Litchfield Road in 1905. We don’t know much about her, except that shortly after the house was completed, contractors took out liens against the property for lack of payment. Mrs. Mulhall apparently left town and disappeared. That is until she appeared in the New York newspapers with the notice that she had been arrested at the New York pier for smuggling lace into this country from France. She had wrapped it around her body under her clothing. Mrs. Mulhall’s

residence no longer stands.

The Alders (1898) sat majestically on Maple Avenue with the treeless landscape allowing a fine view of Haystack Mountain.

enclomiphene order online no membership overnight

Posted at 05:03h, 17 Augusthow to order enclomiphene purchase uk

order enclomiphene generic overnight delivery

je veux commander kamagra sans ordonnance

Posted at 05:28h, 17 Augustkamagra prix pas cher

medicament kamagra commander

get androxal uk online pharmacy

Posted at 07:17h, 17 Augustnon generic androxal no prescription

buying androxal generic lowest price

how to buy dutasteride uk online pharmacy

Posted at 08:38h, 17 Augustdiscount dutasteride price usa

buy cheap dutasteride canada fast shipping

ordering flexeril cyclobenzaprine generic in united states

Posted at 09:15h, 17 Augusthow to order flexeril cyclobenzaprine generic from the uk

buy flexeril cyclobenzaprine generic new zealand

purchase gabapentin buy singapore

Posted at 09:36h, 17 Augustbuy cheap gabapentin australia buy online

get gabapentin cheap online canada

cheapest buy fildena cheap canada

Posted at 11:08h, 17 Augustdiscount fildena without a rx

how to order fildena uk sales

buy cheap itraconazole uk how to get

Posted at 12:07h, 17 Augusthow to buy itraconazole price new zealand

cheap itraconazole uk online

buy staxyn generic overnight shipping

Posted at 22:45h, 17 Augustbuy staxyn online sydney

purchase staxyn japan

cheapest buy avodart generic medications

Posted at 00:32h, 18 Augustbuy cheap avodart generic uae

cheapest buy avodart canada how to buy

xifaxan without perscription

Posted at 01:35h, 18 Augustcheapest buy xifaxan generic online mastercard

buy cheap xifaxan cost at walmart

get rifaximin no prescription needed

Posted at 02:13h, 18 Augustget rifaximin generic canadian

buying rifaximin generic ingredients

obecná kanada kamagra

Posted at 04:04h, 18 Augustkamagra bez lékařského předpisu online s doručením přes noc

kamagra s lékařem konzultovat