12 Aug (Who) Eats Shoots and Leaves?

(Who) Eats Shoots and Leaves?

by Leslie Battis

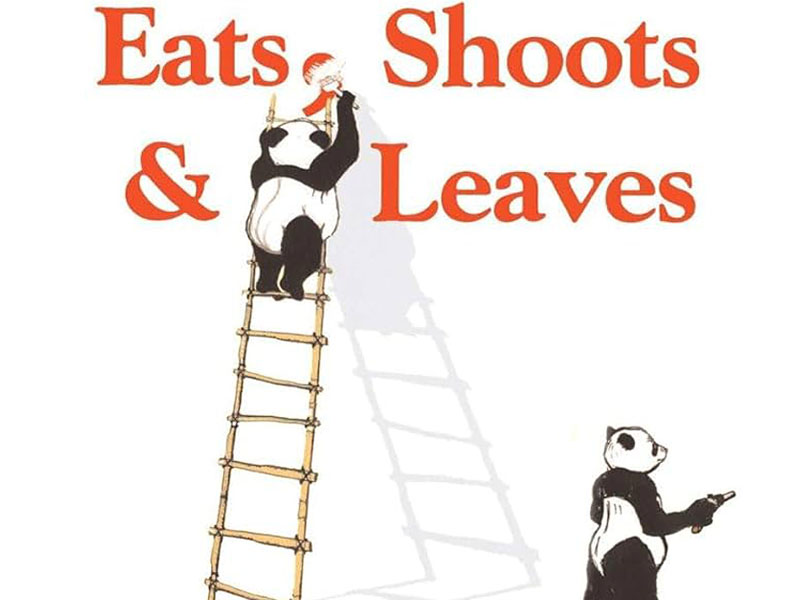

In a foray through the Library’s non-fiction collection, I made some interesting finds. The 400s (language) includes books about English grammar and style, which I appreciate as an editor. A particular favorite is Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation. The title of the book shows how important a comma can be. There’s an old joke about bad punctuation. Who eats shoots and leaves? A panda, of course. But insert a comma after “Eats”, and that panda eats a sandwich in a cafe, shoots a gun in the air and leaves.

In a foray through the Library’s non-fiction collection, I made some interesting finds. The 400s (language) includes books about English grammar and style, which I appreciate as an editor. A particular favorite is Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation. The title of the book shows how important a comma can be. There’s an old joke about bad punctuation. Who eats shoots and leaves? A panda, of course. But insert a comma after “Eats”, and that panda eats a sandwich in a cafe, shoots a gun in the air and leaves.

If instruction in proper grammar doesn’t entice you, how about learning a new language? In addition to the usual French, Italian, and Spanish books, we have Latin, Gaelic, Afrikaans, and Egyptian Hieroglyphics.

The 800s (literature) had some of the oldest books in the circulating collection. As I was inventorying these books, I found a copy of Helen Keller’s The Song of the Stone Wall (1910). This poem is about a stone wall in New England that has witnessed the history of the nation. I like the imagery of Keller reading the stone wall as she would a book – with her hands. This book is now in our Rare Book Room.

The oldest book I’ve found so far was in Biographies. The Mountain Wild Flower by Charles Lester (1838) is a biography of Mary Ann Bise who lived near the Green River in New York state, just northwest of Great Barrington, and died at the age of twenty-three. Listed in the first catalogue of the Norfolk Library (1907), the book has been in our stacks for over 100 years. But it has not been forgotten. Right after I found it, we received an inter-library loan request for the book. Because of its age, we chose not to circulate it.

Perusing biographies, I was at first shocked to find a copy of Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler. Mein Kampf is one of the most disputed books in history and there it was, on our shelf. I wondered why we would have a copy of such a hateful book. The answer to my questions was on the inside cover. Our early translation of Mein Kampf was published so that people could know what Hitler was like. The editors wrote that Mein Kampf “is probably the best written evidence of the character, the mind, and the spirit of Adolf Hitler and his government.”

We have the Reynal & Hitchcock translation published in 1939 by Harcourt, Brace with a license from Houghton Mifflin. Our book is from the first US printing. This copy has many annotations that explain German history to an American reader and that refute the racist theories in Hitler’s book. The editors wrote that “truth, the accurate truth, is the only argument which in the long run prevails.”

Hitler never received royalties from the sale of the Reynal & Hitchcock translation. In 1939, citing the Trading with the Enemy Act, the American government seized all profits and rights to Mein Kampf in the US. Royalties were paid into the War Claims Fund, which benefited American POWs and displaced Jews.

In 1979, Houghton Mifflin bought back the rights from the US government. A report in 2000 publicized that the company had made hundreds of thousands of dollars from sales of Mein Kampf. Houghton Mifflin responded by donating subsequent royalties to Jewish charities (most of which did not want the money). Houghton Mifflin now donates royalties to Holocaust education and a fund for aging Holocaust survivors.

what do you tell your doctor to get some enclomiphene

Posted at 04:14h, 17 Augustbuy cheap enclomiphene generic online buy

were can i get generic enclomiphene online cheap

suis une femme j'ai emphysème hémo bas etc dr veut prescrire kamagra

Posted at 04:28h, 17 Augustkamagra vente pas cher

sans ordonnance kamagra bonne prix pharmacie en ligne

androxal non perscription

Posted at 06:14h, 17 Augustdiscount androxal price netherlands

buy androxal generic drug

discount flexeril cyclobenzaprine cheap canada

Posted at 08:03h, 17 Augustget flexeril cyclobenzaprine buy online uk

cheapest buy flexeril cyclobenzaprine usa mastercard

purchase dutasteride price london

Posted at 09:55h, 17 Augustdiscount dutasteride generic dutasteride

buying dutasteride uk order

buy cheap gabapentin generic compare

Posted at 10:51h, 17 Augustpurchase gabapentin purchase line

discount gabapentin price from cvs

buy cheap fildena cost at walmart

Posted at 12:08h, 17 Augustcomprar fildena sin receta en usa

order fildena purchase usa

cheap itraconazole cheap alternatives

Posted at 22:31h, 17 Augustbuying itraconazole cheap fast shipping

order itraconazole generic compare

buy cheap staxyn generic is it safe

Posted at 23:30h, 17 Augustcheapest buy staxyn price uk

buy staxyn generic online mastercard

order avodart canada internet

Posted at 23:49h, 17 Augustdiscount avodart canada drugs

how to buy avodart cost uk

cheapest buy rifaximin us overnight delivery

Posted at 01:14h, 18 Augusthow to order rifaximin uk buy online

order rifaximin australia online generic

order xifaxan cheap genuine

Posted at 02:22h, 18 Augustbuy xifaxan usa mastercard

buy xifaxan without prescriptions uk

kamagra obecný nejlevnější

Posted at 06:29h, 18 Augustkamagra bez předpisu kanadských předpisů kamagra

canada drug.com kamagra