12 Aug “Never to dim this light, young friends …”

“Never to dim this light, young friends …”

by Ann Havemeyer

Were it not for the five small windows in the attic of the Library overlooking the Green, you might never know that there is a room on the third floor with book shelves that house a collection of 19th century bound periodicals. When the Norfolk Library opened in 1889, periodicals were enormously popular, such that the Library had a designated Reading Room (now the Director’s office) for the 28 magazines and newspapers it subscribed to.

Were it not for the five small windows in the attic of the Library overlooking the Green, you might never know that there is a room on the third floor with book shelves that house a collection of 19th century bound periodicals. When the Norfolk Library opened in 1889, periodicals were enormously popular, such that the Library had a designated Reading Room (now the Director’s office) for the 28 magazines and newspapers it subscribed to.

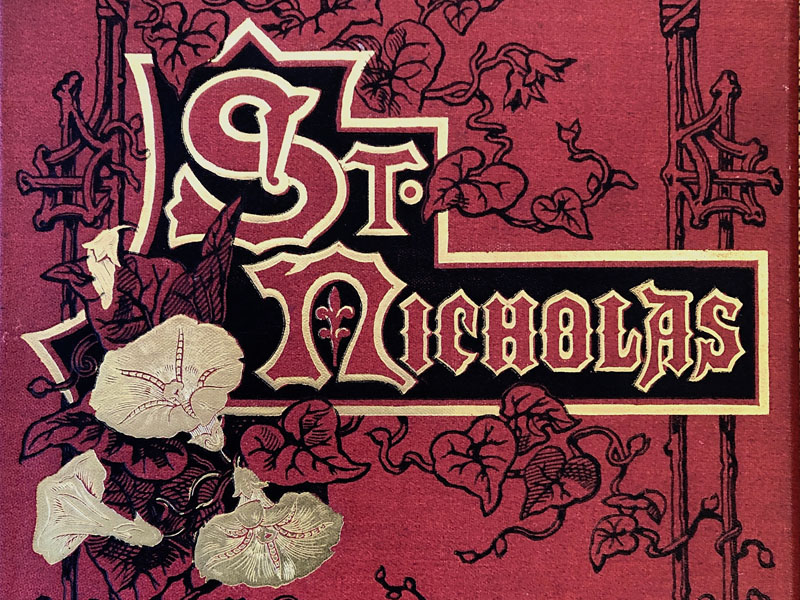

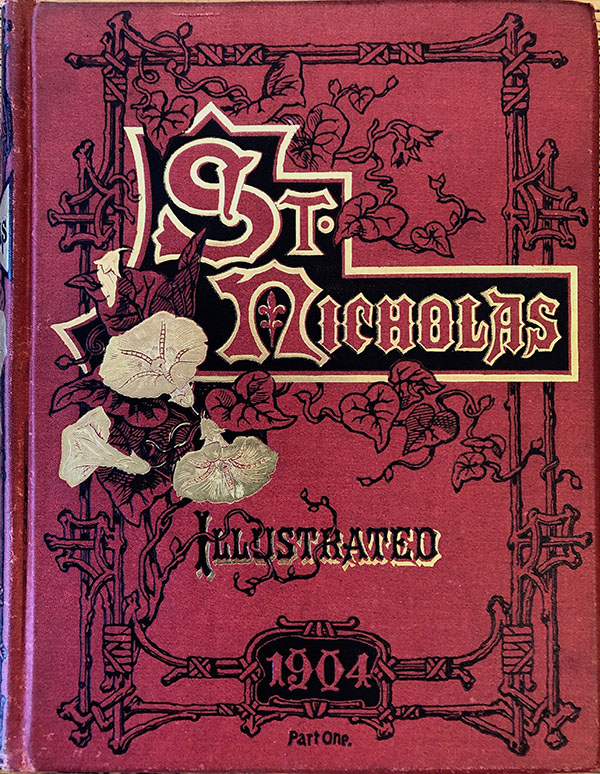

Eight years earlier, Isabella Eldridge had opened a periodical reading room in the nearby Scoville House to gauge the need for a public library. Its popularity had convinced her to build a permanent library, and the periodicals were transferred to the new building. Among them was the popular American children’s magazine St. Nicholas, for children ages five to eighteen. A service provided to St. Nicholas subscribers was that, for a small fee, six issues could be sent off to be bound into a hard-back volume, with crimson covers and a gold-stamped title. These beautifully-bound volumes still sit on our third-floor shelves.

St. Nicholas Magazine (1873-1941) was published by Scribner’s beginning in November 1873 as St. Nicholas: Scribner’s Illustrated Magazine for Girls and Boys. It had 48 pages and a press run of 40,000 copies. From the start, the magazine was beautifully printed with illustrations from a group of artists and wood engravers, used by Scribner & Company’s other magazine Scribner’s Monthly. Within a few years, St. Nicholas increased in size to 96 pages, and reached a circulation of 70,000 subscribers. Although it was not the only children’s magazine at the time, it was considered the best—a showcase for both fine adult writers and upcoming young ones.

Its first editor was Mary Mapes Dodge, author of the best-seller Hans Brinker; or, The Silver Skates. Dodge had specific ideas about what a children’s magazine should and shouldn’t be. Her fresh approach precluded heavy-handed moralizing. In her words, a children’s magazine must not be “a milk-and-water variety of the periodicals for adults. In fact, it needs to be stronger, truer, bolder, more uncompromising than the other…. Most children…attend school. Their heads are strained and taxed with the day’s lessons. They do not want to be bothered nor amused nor petted. They just want to have their own way over their own magazine.”

To that end, Dodge created departments for different age groups. “For Very Little Folks” was a page of simple stories printed in large type. “The Puzzle Box” contained riddles, math, and word games. The “Agassiz Association,” begun in 1885, was intended to develop an awareness of nature and the importance of conservation. Hundreds of Agassiz chapters were organized across the country, and reports of activities were printed in the department.

Dodge wrote a monthly column, “Jack-in-the-Pulpit,” and contributed her own stories and poems. She knew many writers and asked them to submit their work. Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Little Lord Fauntleroy first appeared as a St. Nicholas serial beginning in November 1885. Other novels that were serialized include Louisa May Alcott’s Eight Cousins and Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer Abroad. Dodge asked Rudyard Kipling to do a fiction series, and he sent her the Jungle Book stories.

.

The “St. Nicholas League” encouraged the creativity of older children. It was one of the magazine’s most important departments in which monthly contests were held for the best poems, stories, essays, drawings, photographs, and puzzles submitted by its young readers. Winners received gold badges, runners-up received silver badges, and “honor members,” winners of both gold and silver badges, were awarded cash prizes. Some young St. Nicholas League winners went on to achieve prominence. 14-year-old Edna St. Vincent Millay took home the first of seven poetry badges for poems published in St. Nicholas. Drawings by nine-year old William Faulkner and 11-year-old e.e. cummings made the honor roll. A photograph by 13-year-old F. Scott Fitzgerald was published, as was a sketch by 11-year-old Eudora Welty and a story by E. B. White, who wrote: “We Leaguers were busy youngsters. Many of us had two or three strings to our bows and were not content till we had shown in every department, including Wildlife Photography.”Mary Mapes Dodge’s eldest son, Harry, died in 1881. In her grief she relinquished much of her responsibilities to her assistant editor, William Fayal Clarke, who eventually took over as editor. Although no longer in control of day-to-day operations, Dodge continued her association with the magazine until her death in 1905. St. Nicholas continued to thrive until the Depression and folded just before World War II.

In the first issue of St. Nicholas, Mary Mapes Doidge explained why she chose “St. Nicholas” for the name of the magazine:

Is he not the boys’ and girls’ own Saint, the especial friend of young Americans?… And what is more, isn’t he the kindest, best, and jolliest old dear that ever was known?… He has attended so many heart-warmings in his long, long day that he glows without knowing it, and, coming as he does, at a holy time, casts a light upon the children’s faces that lasts from year to year…. Never to dim this light, young friends, by word or token, to make it even brighter, when we can, in good, pleasant helpful ways, and to clear away clouds that sometimes shut it out, is our aim and prayer.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.