12 Aug Feeling Blue?

Feeling Blue?

by Leslie Battis

Merriam-Webster lists no fewer than nine definitions of the word “blue.” In the context of the question above, it clearly means “melancholy.” In the 19th century, it sometimes meant “intellectual.” William Thackeray wrote: “the ladies were very blue and well-informed.” But it is the18th-century usage of the word blue – rigidly moral – from which the title of one of the more interesting books in our non-fiction collection is derived.

Merriam-Webster lists no fewer than nine definitions of the word “blue.” In the context of the question above, it clearly means “melancholy.” In the 19th century, it sometimes meant “intellectual.” William Thackeray wrote: “the ladies were very blue and well-informed.” But it is the18th-century usage of the word blue – rigidly moral – from which the title of one of the more interesting books in our non-fiction collection is derived.

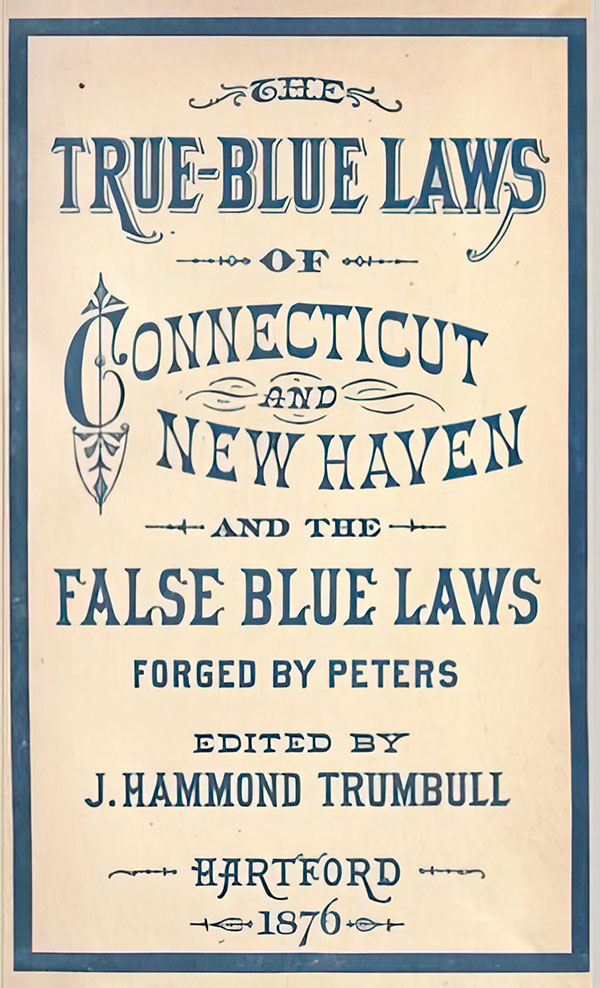

Our edition of The Blue Laws of Connecticut was published in 1861, more than 200 years after the 1655 New Haven Code of Law on which it is based. One might wonder why 200-year-old laws would be reprinted. According to the preface, “a new impression was deemed desirable to meet the frequent calls which were made for it.”

The New Haven Code of Law prohibited business from being conducted on Sundays and guarded against personal moral offences such as public drunkenness: “No person licensed for common interteinment, shall suffer any to drinke excessively viz. above halfe a pinte of wyne, … or to continue tipling above the space of halfe an houre” on penalty of five shillings.” This would certainly raise some good tax revenue if implemented today!

It is unknown when the term “blue laws” was first used to describe the New Haven Code of Law, although several theories have been advanced. But Connecticut’s blue laws received international notoriety after their inclusion in Reverend Samuel Peters’s General History of Connecticut (1781). Having been forced by the Sons of Liberty to leave Connecticut in 1774, Peters relocated to England and published 45 blue laws that he claimed were Connecticut’s law of the land. Some were outlandish: “Every male shall have his hair cut round, according to a cap” and when caps were not available the puritans were to “use the hard shell of a pumpkin, which being put on the head every Saturday, the hair is cut.” His work reinforced the contemporary English view of Americans as fanatical dolts in need of repressive legislation.

While Peters’s account of the New Haven Puritan government’s code has been proven unreliable, there are a few laws that were substantially true: “married persons must live together or be imprisoned”; “a wife shall be good evidence against her husband”; and “the selectmen, on finding children ignorant, may take them away from their parents and put them into better hands, at the expense of their parents.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.