12 Aug Button Up!

Button Up!

by Leslie Battis

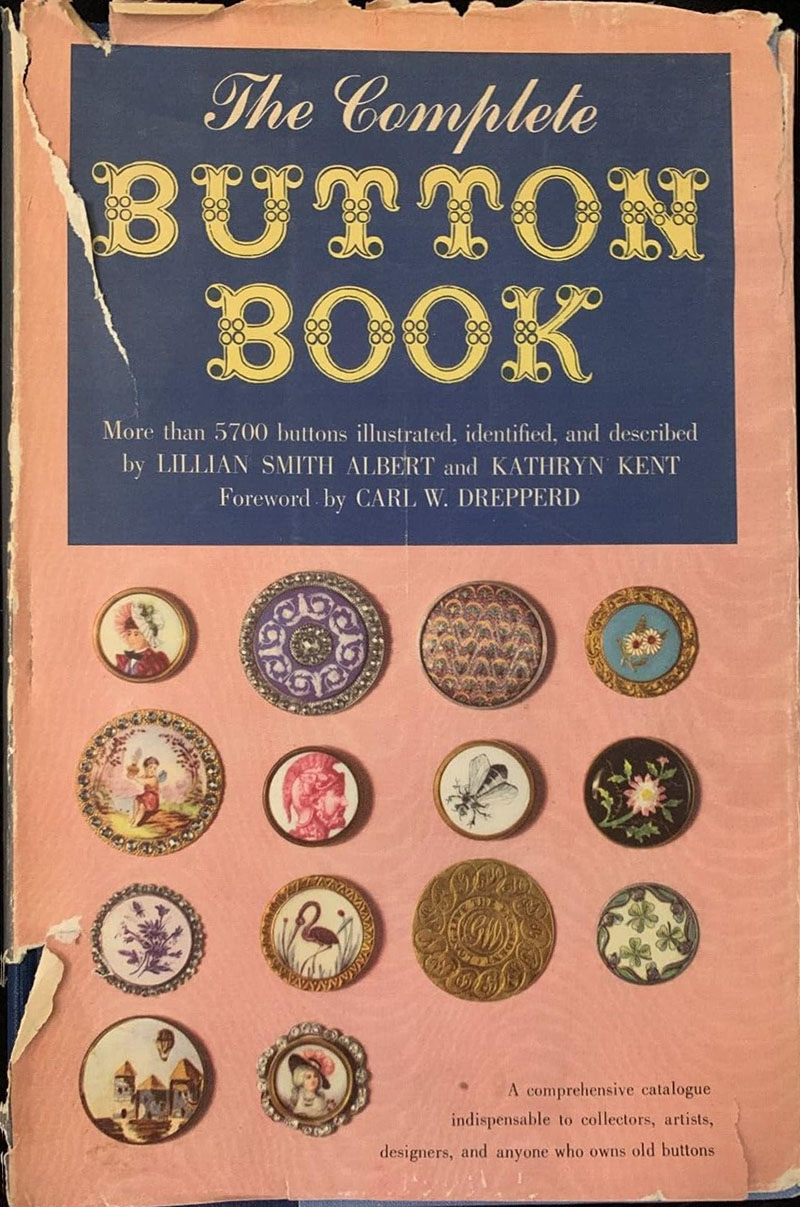

There’s more to buttons than you may think. I discovered this when I happened upon an unusual volume in the library collection: The Complete Button Book by Lillian Smith Albert and Kathryn Kent, published in 1949. A whole book that is devoted to buttons? Why not! We also have books devoted to early American andirons, New England doorways, thimbles, and artificial soft paste porcelain. We are a library after all!

The Complete Button Book is for button collectors. The book has sections about the history of buttons and methods of manufacturing. But mostly it is dedicated to black-and-white photos of buttons. For a more colorful approach to the history of buttons, I turned to another volume in our collection, English Costume Painted and Described by Dion Clayton Calthrop, published in 1907. English Costume traces the history of English clothing from 1066 to 1830 with paintings of the typical fashion during the reign of each King and Queen. In the introduction to English Costume, Calthrop summarizes the book as a history of fashion that follows “the changes of the garments reign by reign, fold by fold, button by button.” Between these two books, I learned that small details, such as buttons and buttonholes, can lead to big changes.

Until buttonholes were invented in the 13th century, garments in Medieval Europe were laced together, fastened with pins, or pushed into a loop of fabric. Extensive draping of lots of fabric denoted wealth. Calthrop describes the reign of Henry the Third (1216-1272) as a transitional period in the history of clothes: “as in its course the draped man developed very slowly towards the coated man, and the loose-hung clothes very gradually began to shape themselves to the body.” The buttonhole quietly changed fashion.

By the mid-13th century, buttons were in everyday use. Buttons down the front of a lady’s dress could be made of fabric, metal, or semiprecious stones. Rather than lots of fabric, the wealthy exhibited fancy buttons as status symbols. In the 15th century, buttons became such a popular status symbol of wealth that sumptuary laws were passed to control excessive displays of buttons. Except for the king, of course. In 1520, the King of France wore an outfit with 13,600 buttons and the corresponding hand-stitched 13,600 buttonholes.

For the common people, buttons were made at home out of wood or bone until the Industrial Revolution. The Complete Button Book describes the methods of manufacturing different types of buttons: metal, bone, wood, leather, ceramic, enamel, fabric, glass, and pearl. In the section about metal buttons, we learn about the Waterbury Button Company.

When the War of 1812 interrupted the supply of metal buttons coming into the United States from England, Aaron Benedict of Waterbury, Connecticut, began producing brass buttons for military uniforms. His firm would become the Waterbury Button Company, which was established in 1849. By the time General Ulysses S. Grant met General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Courthouse in 1865, both men wore Waterbury buttons on their coats.

The Waterbury Button Company continues to make buttons for all branches of the U.S. Armed Forces. They are the oldest metal-button manufacturer in the United States that is still in business. When the Titanic sailed in 1912, the 100-year-old Waterbury Button Company was asked to make the buttons for the double-breasted coats of crew. In 1997, the company used the same dies to make the buttons for the actors portraying the ship’s crew in the movie Titanic.

In 1999, the Waterbury Button Company donated their 20,000-button collection to the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury. The Norfolk Library has two free passes to the museum where you can see more than 3,000 buttons on display.

The Complete Button Book by Lillian Smith Albert and Kathryn Kent

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.