12 Aug Survival in the Arctic

Survival in the Arctic

by Ann Havemeyer

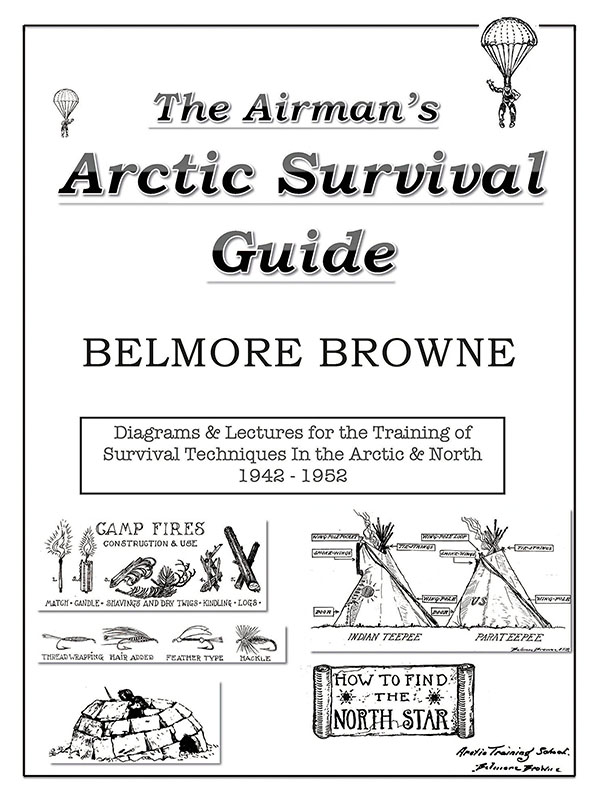

Although we do not anticipate needing a guide for surviving arctic conditions here in the Icebox of Connecticut, there is a Norfolk connection to the man who penned The Airman’s Arctic Survival Guide: Diagrams and Lectures for the Training of Survival Techniques in the Arctic and North.

Although we do not anticipate needing a guide for surviving arctic conditions here in the Icebox of Connecticut, there is a Norfolk connection to the man who penned The Airman’s Arctic Survival Guide: Diagrams and Lectures for the Training of Survival Techniques in the Arctic and North.

Belmore Browne (1880-1954), artist, explorer, and mountaineer, prepared 38 hand-drawn illustrations for the training in survival techniques in northern climates to USAAF and USAF airmen during World War II and the Korean War. The illustrations included demonstrations of shelters, emergency tools and equipment, fire building, and wilderness travel. They were designed to accompany Belmore’s training lectures as Air Force instructor in the high mountains of Colorado. They were also distributed as posters to airbases throughout Canada, Alaska, and Greenland. As a result, Belmore taught many thousands of men the simple but essential things necessary for wilderness survival.

With a lifetime of experience in the wilderness of Alaska and the Canadian Rockies, Belmore was eminently qualified for the task of training airmen, rescue personnel, and mountain troops for survival in northern and winter conditions. He learned his wilderness skills from Native guides in Alaska, which he first visited with his family when he was eight years old.

Belmore was born in Tompkinsville, Staten Island, to George and Susan Browne. As a broker, importer, and member of the New York Stock Exchange, George Browne earned a significant fortune that gave him the means to pursue his interests, painting and architecture. In 1883, he and his family relocated to Europe, traveling around France, Italy, and Switzerland. They returned to the United States five years later and settled in the Pacific Northwest. George used his investments to help found the St. Paul and Tacoma Lumber Company, and the children were sent to private schools in New England.

At age eighteen, Belmore decided to pursue art as a career. He received formal training at the New York School of Art and the Académie Julian in Paris. A skilled outdoorsman, Belmore combined his work as an artist with his passion for the wilderness. He joined several expeditions in the unexplored areas of the Pacific Northwest and was part of a group that made the first ascent of Washington’s Mount Olympus. In 1902, he participated in Andrew J. Stone’s mammal-collecting expeditions in Alaska for the American Museum of Natural History, putting his artistic skills to use in making accurate anatomical drawings of different animals. In a painting that now hangs in the Smithsonian Institute, he commemorated a ride he took down Alaska’s Stikine River with Chief Shakes of the Tlingit Indian tribe in his keahtyant (war canoe).

Belmore made three attempts to summit Mount McKinley, now Denali, in 1906, 1910, and 1912, which he recorded in The Conquest of Mount McKinley (first published in 1913). The 1912 expedition was by dog-sled in the dead of winter from Seward on the coast 400 miles to the north side of Mt. McKinley. The men made it to within 300 yards of the summit when snowstorms forced them to retreat.

In 1913, Belmore returned east to marry Agnes Sibley of Philadelphia, and the couple settled in New York where their children Evelyn and George were born. After service in the First World War as captain in the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps, Belmore and the family moved to Banff, where he immersed himself in his art. Agnes later recalled that this was the most productive period of his artistic career. He painted outdoors, even in winter, when he often needed to wear multiple pairs of socks on his hands “with the brushes pulled through so that he could move his fingers easily within the socks” (Ordeman and Schreiber, George and Belmore Browne: Artists of the North American Wilderness, 2004). His best-known paintings show scenes of Alaska, the Northwest, and the Canadian Rockies.

Belmore eventually began to spend winters in California with his family and was named director of the Santa Barbara School of Fine Arts in 1930. Just before World War II, he was commissioned to paint several backgrounds for big-game exhibits in the North American Hall of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The detail and realism with which he portrayed nature are evident in the dioramas he created with his son George. His last diorama, painted just before his death in 1954, was for a new black bear exhibit at the Museum of Science in Boston.

George followed in his father’s footsteps. Belmore had encouraged his son’s love of the wilderness and taught him how to paint, even though George’s vision was limited because of a childhood injury to his left eye. On summer camping excursions with his family, and during winter days in northern California, George spent much of his time sketching. At age fifteen, with the support of his parents, he quit school, began an apprenticeship under his father, and then enrolled in the California School of Fine Arts. Belmore and George were inseparable companions on the trail in the Canadian Rockies, always handling their own pack train and camping in many upland valleys where they painted well into the fall each year.

In 1947, after his discharge from the army, George reached the 20,320-foot summit of Mount McKinley as part of a Bradford Washburn-led scientific expedition. What is remarkable about this climb is that he created 23 oil paintings along the way. In addition to his climbing gear and food, he carried canvases, brushes, paint, and an easel. As the group ascended the mountain, he painted during periods of good weather, only abandoning his task when, at 11,000 feet with temperatures at 20-below zero, his paint froze. He carried the painted canvases in a plywood box designed so the wet paintings wouldn’t smear in transit.

One year later, in 1948, George married San Francisco-native Isabel (Tibby) McGregor, and the couple moved to Seebe, Alberta. They had two children, Isabel (Busy) and Belmore. As his work gained recognition, George and the family moved to Norfolk, where family friend and fellow sportsman Frederick K. Barbour lived, to be nearer to the hub of the sporting art industry. Through the 1950s, he had several one-man shows and sold over 200 paintings at art galleries in North America and Canada, emerging in the art world as a gifted painter particularly for his portrayals of waterfowl and upland game birds.

Tragically, George was killed in 1958 at a weekend gathering in the Adirondack Mountains of New York State. An acquaintance unfamiliar with firearms accidentally discharged a bullet from his gun, which hit George in the neck. He was just 40 years old.

Tibby remained in Norfolk and later married Hugh Robinson. She was devoted to the Library and served on the Board of Trustees, masterminding the Library’s Second Century Support campaign in the 1980s which raised funds for the addition of the Children’s Room.

Two of George Browne’s paintings are in the Library collection. The Airman’s Arctic Survival Guide: Diagrams and Lectures for the Training of Survival Techniques in the Arctic and North was published in book form in 2014, Editors Isabel Browne Driscoll, granddaughter of Belmore Browne, and Peter Driscoll assembled material from family and other archival collections, including the Browne Family Collection and the Belmore Browne Papers at the Dartmouth College Library. Isabel and Peter presented a copy of the book to the Library in memory of Tibby Robinson.

Autumn Afternoon by George Browne, Collection of the Norfolk Library

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.