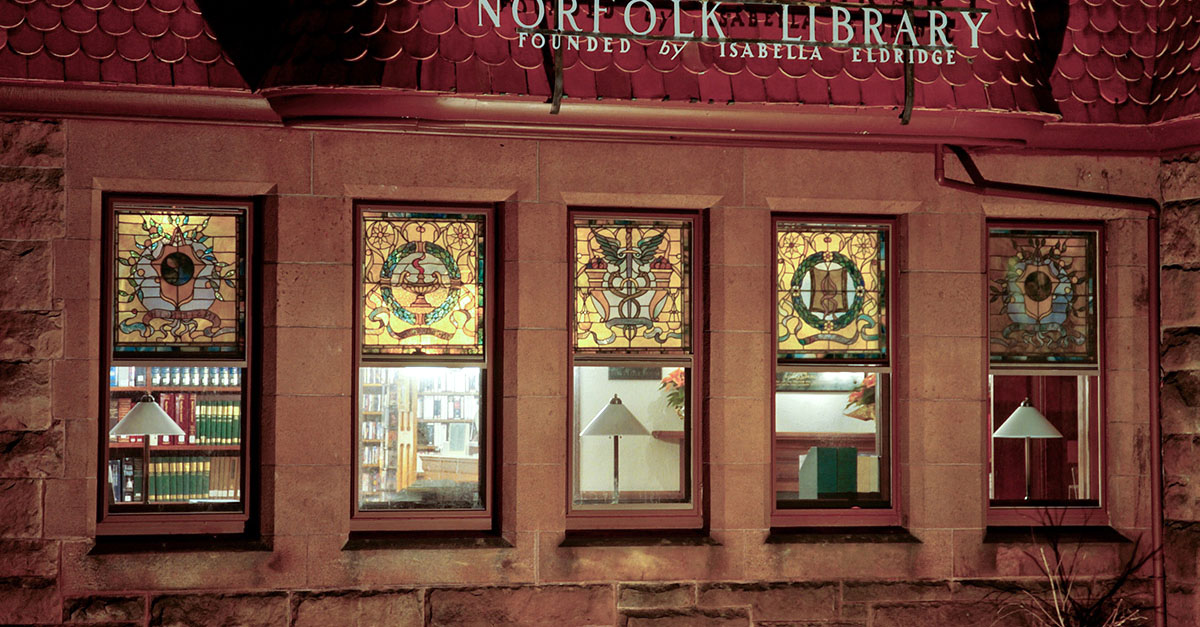

Built in 1888, the Norfolk Library has been the centerpiece of Norfolk’s impressive architectural tradition for over a century. Drivers passing through town for the first time have been known to stop at our front door wondering at the delightful building. Even residents of Norfolk and neighboring communities find themselves marveling anew at the beauty of our library–inside and out. For this we thank Isabella Purple Eldridge (1848-1919), who saw the need for a library in Norfolk and engaged a noted architect to design it.

Norfolk Library History & Architecture

Norfolk Library, circa 1890

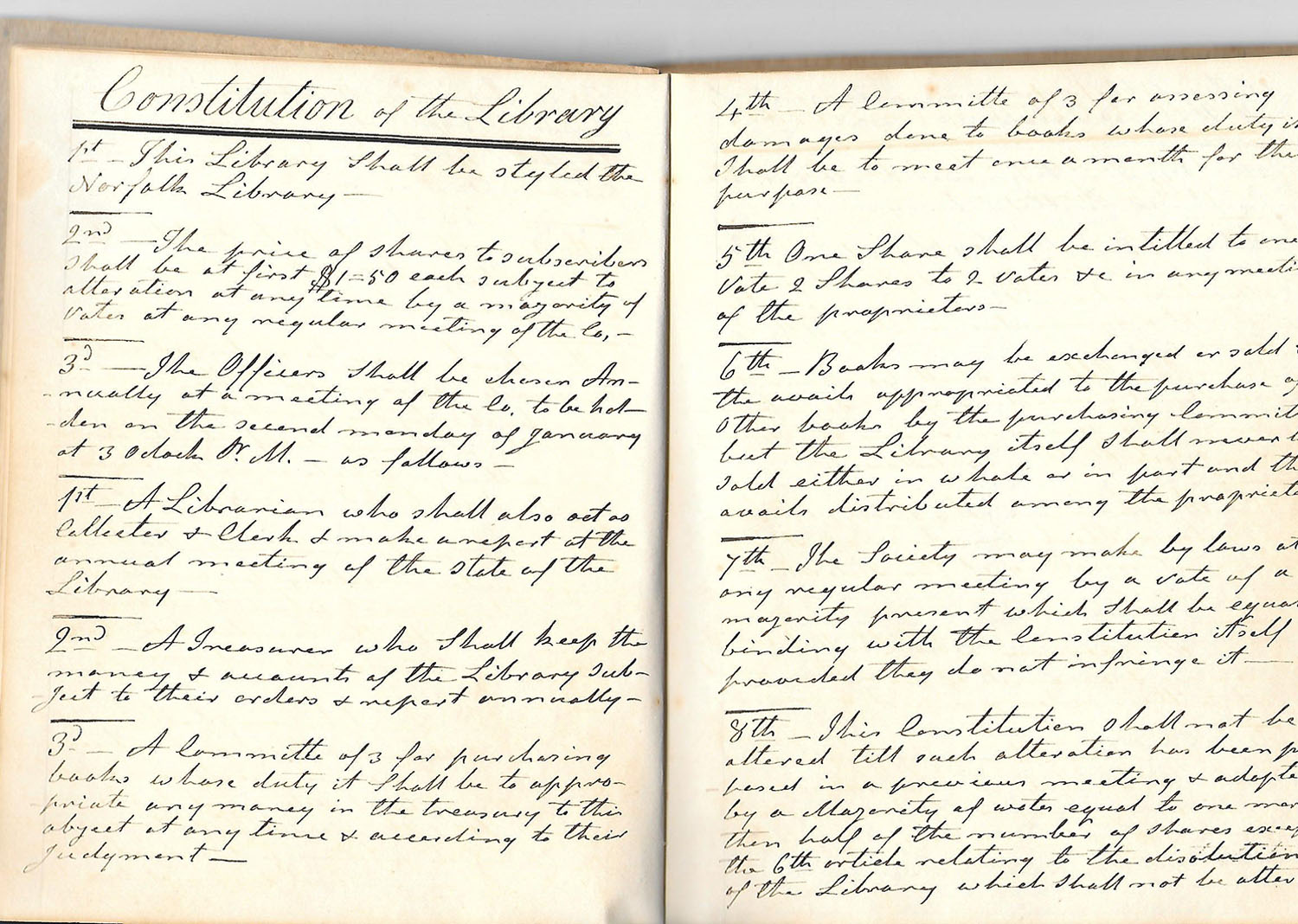

1822 Norfolk Library Constitution

During Isabella’s childhood, Norfolk did not have a proper library. Three years after the town’s incorporation in 1758, a library company was established with a collection of 150 books that circulated in private homes and was available only to members. The company dissolved in the 1790s. In 1822, a second library company was incorporated. Like its predecessor, it was mobile: books were kept in an oak cupboard, which was moved from house to house. The company had a written constitution, and members were charged a yearly fee of one dollar or had the option of adding one volume to the collection. Isabella’s mother, Sarah Eldridge, was on the committee appointed to purchase books.

Isabella was the daughter of the Reverend Joseph Eldridge, beloved pastor of Norfolk’s Church of Christ, and Sarah Battell Eldridge. She grew up in the parsonage where her father kept a remarkable collection of books, freely used by his parishioners. Knowing its potential value, Isabella opened a public reading room in 1881 in the Scoville house on Greenwoods Road, across from where the Library now stands. Along with books, she stocked it with the latest periodicals, which proved to be popular. Its success led to her decision to build and endow a permanent library as a tribute to her recently deceased parents.

Isabella Eldridge (F. Roseti, New York) is pictured in the dress she wore to the opening of the Library, March 6, 1889.

Bushnell Memorial Arch, color postcard

In 1888 Isabella commissioned nationally known Hartford architect George Keller (1842-1935) to draw plans for the building. Four years earlier he had won the prestigious competition to design the James A. Garfield Memorial in Cleveland, and his Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch in Bushnell Park had been dedicated in 1886. Yet in spite of Keller’s renown, Isabella’s decision to engage him as architect was a bold one. He had not practiced in the northwest corner of Connecticut, he had never designed a library, and his materials of choice—brownstone, terra-cotta shingles, and clay roof tiles—were far outside the vernacular typical in rural late nineteenth-century New England villages. His design for Norfolk proved a success and led to commissions for two other libraries: one in Ansonia, Connecticut (1892), and the other in Granville, Massachusetts (1902). David F. Ransom, author of George Keller, Architect (1978), extolls Keller’s libraries as “the crowning achievement of his career.”

The Norfolk Library is an outstanding example of Keller’s clever adaptation of the Richardson Romanesque style. The building’s vibrant appearance is achieved through the variety and rich colors of its exterior materials: East Longmeadow, Massachusetts, brownstone and terra-cotta fish-scale shingles for the walls, and clay pantiles (S-curved tiles) for the roof. Most of the construction came from the hands of local builders—graders Hiram Camp and William Curtiss, stone masons Snow and Wooster, and carpenter James Levi—all superb craftsmen who took pride in their work and ensured that Isabella’s vision was realized masterfully. The cost to build, as reported in the New Haven Palladium, was $25,000. The grand opening of the Library was held on March 6, 1889.

Frank DeMars photograph, ca. 1910

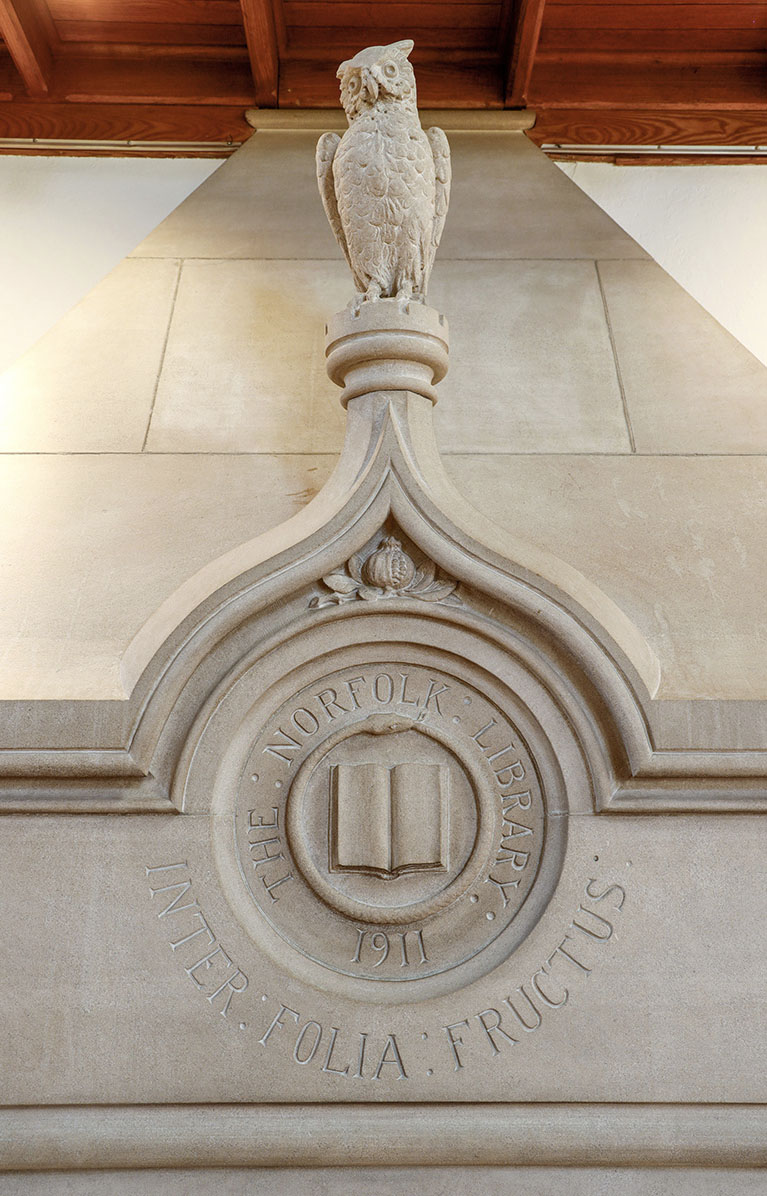

In addition to its striking presence on the townscape, the new library was inviting. Keller designed an entrance porch tucked into the southwest corner, giving it an almost domestic aspect that must have pleased Isabella. A sandstone owl, perched at the corner of the roof, eyes visitors as they step onto the porch. It was created by Hartford architectural sculptor Albert Entress, a frequent collaborator of the architect. Keller specified a variety of finishes for the interior, and the commodious spaces still gleam of warm, polished wood: oak, cherry, and ash. A set of double-hung windows in the front room feature stained glass in the upper sash created by D. Maitland Armstrong, who had recently established a stained-glass company in New York.

In 1911, Isabella asked George Keller to design an addition to the Library. Norfolk had burgeoned as a summer resort, the population more than doubling during the summer months, and she wanted a library and cultural center that could accommodate more people. To this end, she proposed the addition of a large “reading room,” now known as the Great Hall. Keller produced an addition so seamless in appearance that it looks as though it was planned from the beginning. The same exterior building materials were used: brownstone from the East Longmeadow, Massachusetts, quarry and Spanish tile from the Ludowici-Celadon Company’s factory in New Lexington, Ohio.

Hand-colored postcard photograph, ca. 1915

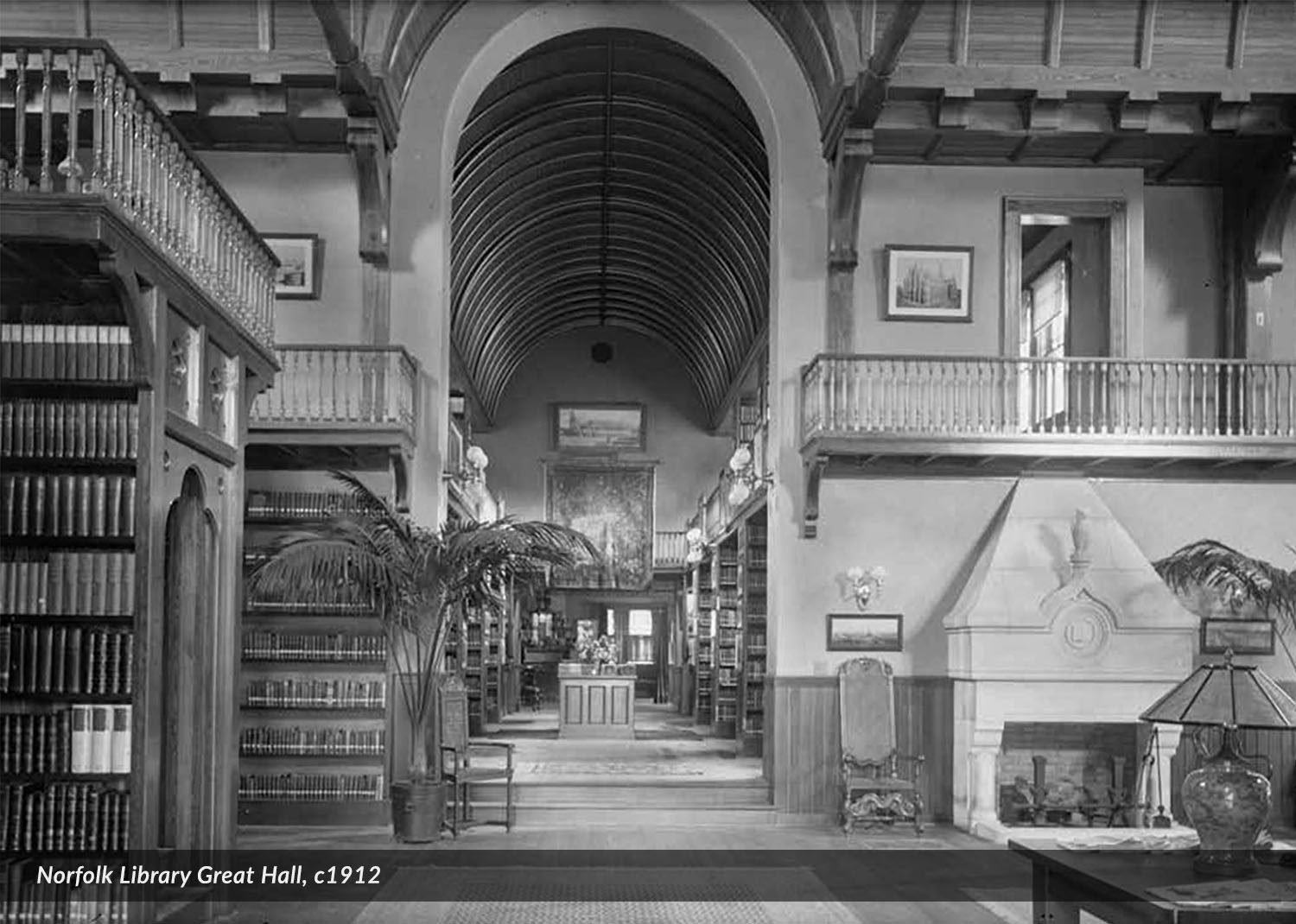

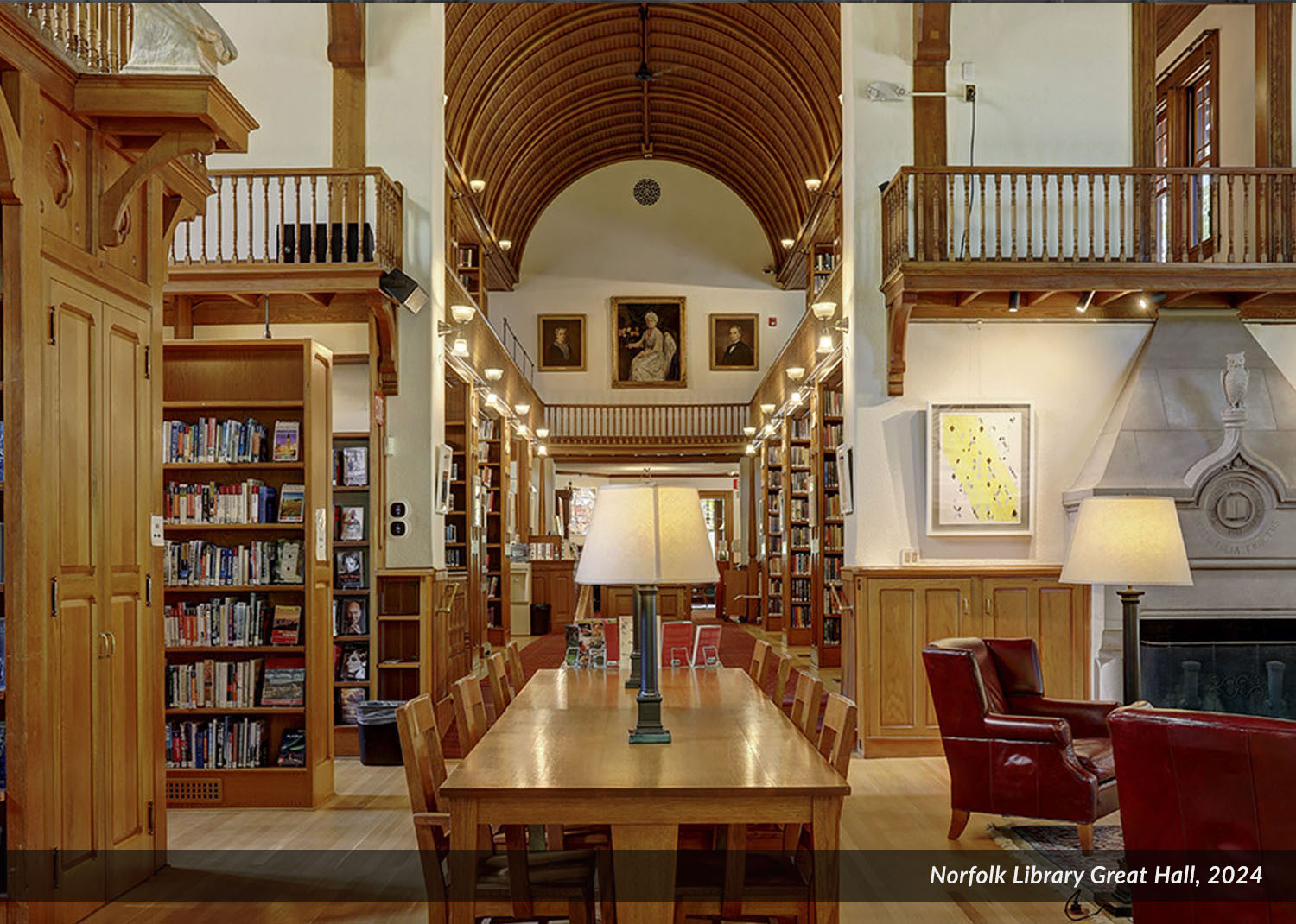

Great Hall

The double-height room with wood barrel-vault ceiling, large cross beams, and an appropriately scaled imposing fireplace gives the effect of a baronial hall. An owl created by Albert Entress sits atop the stone overmantel on which is carved the library emblem and the date 1911. Two large rose windows, designed by Maitland Armstrong, frame the hall.

Then & Now

With its luminous stained-glass windows and barrel-vault ceilings of polished wood, the Library retains the special ambience it had when it was built. Drag the arrows to the right or left for the full photograph.

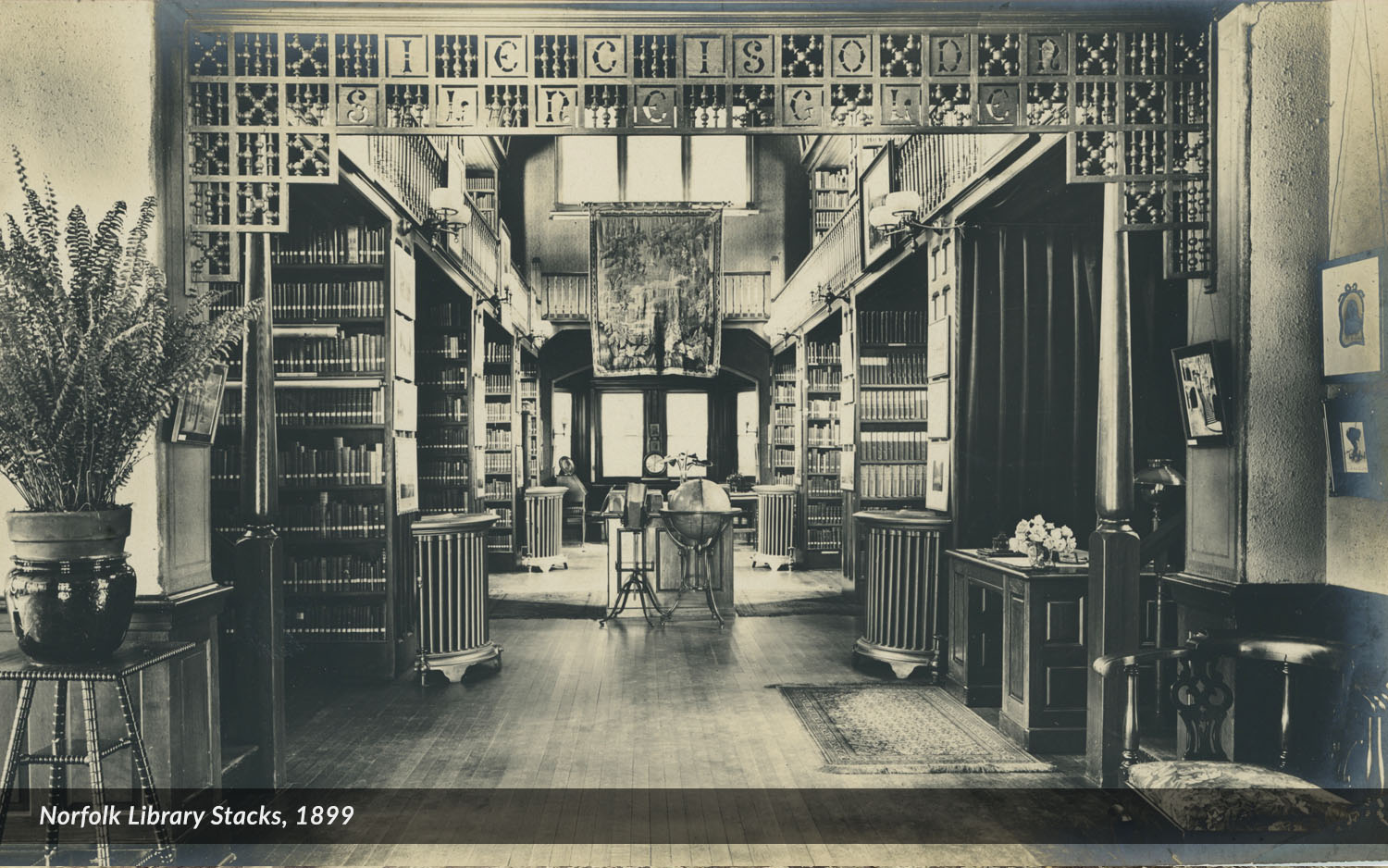

Wooden fretwork that spelled Silence is Golden originally framed the entrance to the main hall.

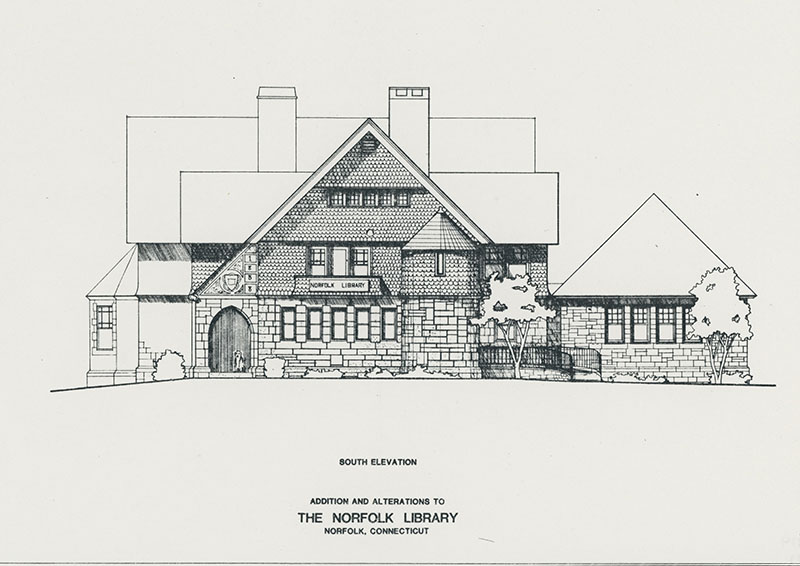

In 1985, the Smith Children’s Room was added to the Library, made possible by gifts from Abel I. Smith and others. Alec Frost, architect with the firm Moore and Salisbury, designed the addition in keeping with the existing building. The abandoned James and Mara quarry in East Longmeadow was reopened to provide us with the same brownstone used back in 1888. Thus, like the Great Hall addition of 1911, the children’s room would meld seamlessly with the exterior of George Keller’s original design. With a hipped roof, the single-story structure opens off the east side of the building on what used to be part of the railroad right-of-way, deeded by the Town of Norfolk to the Library in 1984. Once again, Norfolk builders and craftsmen did much of the work.

Top: Architectural elevation with the Children’s Room on the right, 1985

Library exterior courtyard

Through generous donations by many members of the community and a grant from the Connecticut State Office of Historic Preservation, a restoration of the exterior was undertaken in 2015. Decades of harsh New England winters had taken their toll on the building and the terra cotta roof tiles had been replaced with asphalt shingles. The firm of John G. Waite & Associates, one of the country’s top architectural preservationists, was engaged to undertake the restoration. The asphalt roof shingles were replaced with terra-cotta pantiles, manufactured by the Ludowici Roof Tile Company, of New Lexington, Ohio, which had provided the tiles for the Great Hall addition in 1911. This returned the architectural integrity to the Library, giving the highly visible expansive roof a picturesque treatment as dictated by Victorian design. A second phase of the project included the construction of a new accessible entrance around a courtyard to the west of the building.

Interior improvements have included the 2018 renovation of the Smith Children’s Room with new carpets, shelves, and lights from the cove ceiling suggesting a starlit constellation. In 2023, the alcoves at the north end of the building were reimagined as Owl Coves, a dedicated area for teens with an art wall, technology bar, large screen, and comfortable furniture.

Smith Children’s Room

Norfolk Library Architectural Highlights

Corner entrance porch

The turret houses a circular staircase to the second floor.

The Owl

Albert Entress of Hartford sculpted the gargoyle in the shape of an owl which adorns the front porch, as well as another owl standing over the fireplace in the Great Hall holding a book bearing the library’s motto “Inter Folia Fructus.”

Stained Glass

The stained glass windows in the Harden Reference Room and the Great Hall were made by Maitland Armstrong & Co. of New York City.

Historic Artifacts

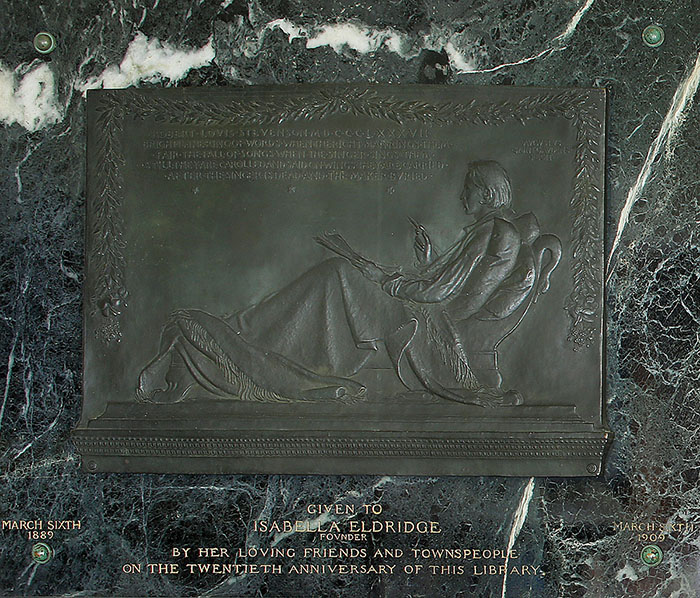

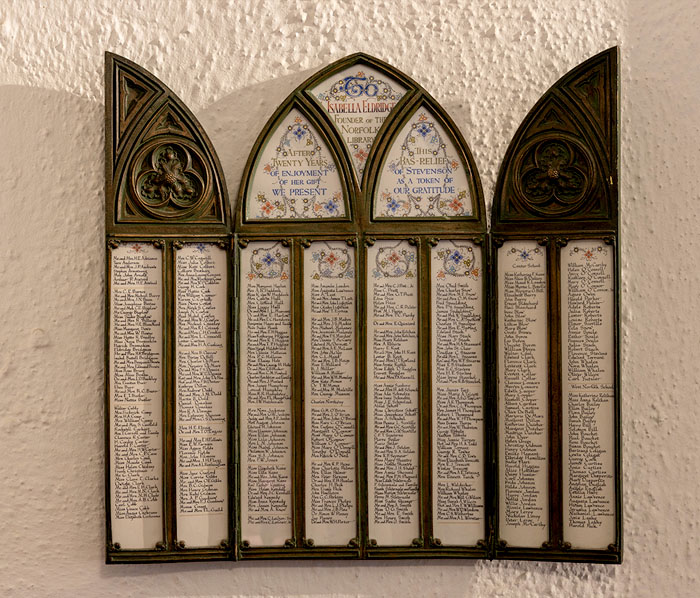

Below left: A plaque depicting Robert Louis Stevenson was designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and presented by townsfolk to Isabella Eldridge in 1909 on the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the Library, along with a illuminated triptych (bottom left).

Below right: The portrait of Isabella Eldridge was painted by Ellen Emmet Rand in 1926.

Bottom right: The large medallion hanging upstairs over the back alcove was created by Tonell in 1917. Called “The War of Democracy,” it was among the parade decorations in New York to welcome the French and British Commissions in 1917 and was given to the Library by Mrs. John H. Flagg.

Norfolk Library Associates

In keeping with Isabella Eldridge’s wish that the Library serve as a cultural meeting spot of Norfolk, the Trustees made provision for the formation of the Norfolk Library Associates in 1974. This devoted and invaluable group sponsors monthly art exhibits by local artists, children’s programs, a book discussion group, and films, concerts, and lectures throughout the year, all with money raised through an annual summer book sale and other fund-raising events. Click here to learn more about the Norfolk Library Associates.